Algorithm of Rate Limiter

Introduction to Rate Limiting

Rate limiting is a mechanism to control the rate of incoming requests to a system, preventing overload and ensuring stability. It acts as a traffic regulator for servers, with the primary objectives of:

- System Protection: Mitigating the impact of traffic spikes, such as during e-commerce flash sales.

- Abuse Prevention: Blocking malicious requests, such as crawlers or denial-of-service attacks.

- Cost Management: Regulating usage of pay-per-request resources, such as cloud APIs.

This document details five prevalent rate-limiting algorithms, providing accessible explanations, technical analyses of advantages and disadvantages, applicable scenarios, Java implementations with comprehensive comments, and Mermaid diagrams to aid understanding.

Overview of Rate-Limiting Algorithms

The following table compares five rate-limiting algorithms based on their advantages, disadvantages, use cases, and computational complexity:

| Algorithm | Advantages | Disadvantages | Use Cases | Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Token Bucket | ✅ Simple Implementation ✅ Supports Bursty Traffic | ❌ Complex Parameter Tuning ❌ Risk of Short-Term Overload | E-commerce flash sales (e.g., Alibaba Double 11), API requests (e.g., X post limits) | O(1) Time O(1) Space |

| Leaky Bucket | ✅ Stable Output ✅ Memory Efficient | ❌ No Support for Bursty Traffic ❌ Increased Request Latency | E-commerce APIs (e.g., Shopify order requests), stable traffic services | O(1) Time O(n) Space |

| Fixed Window Counter | ✅ Simple Implementation ✅ Memory Efficient | ❌ Window Boundary Overload | Simple rate limiting (e.g., 5 login attempts per minute), quota reset scenarios | O(1) Time O(1) Space |

| Sliding Window Log | ✅ High Precision ✅ No Boundary Issues | ❌ High Memory Usage ❌ Complex Implementation | Financial transactions (e.g., stock trading), ad bidding, high-frequency trading | O(n) Time O(n) Space |

| Sliding Window Counter | ✅ Memory Efficient ✅ Smooths Traffic Peaks | ❌ Limited Precision | E-commerce promotions (e.g., JD 618), social media surges (e.g., TikTok trending events) | O(1) Time O(n) Space |

Note: Complexity

nrefers to the number of requests or timestamps.

Detailed Analysis and Java Implementations

1. Token Bucket

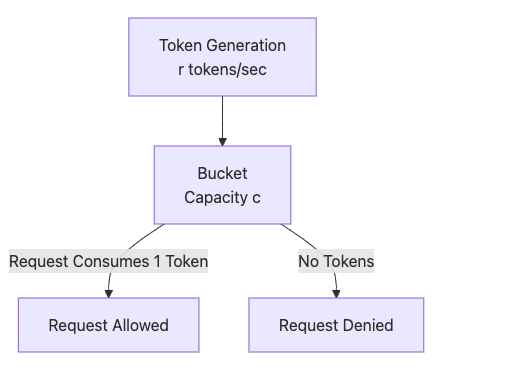

Accessible Explanation:

The token bucket is akin to a ticket dispenser that issues tickets (tokens) at a fixed rate. Each request requires a token to proceed; if none are available, the request is denied. Tokens can accumulate in the bucket, enabling the system to handle bursts of requests, much like a theater allowing a surge of ticketed patrons during a premiere.

Principle: The bucket replenishes tokens at a constant rate. Requests consume tokens, and if insufficient tokens are available, requests are rejected. This supports bursty traffic.

Mermaid Diagram:

Advantages:

- Simple Implementation: Straightforward logic and coding, addressing the challenge of complex rate-limiting designs.

- Supports Bursty Traffic: Accumulated tokens allow handling short-term traffic spikes, ideal for scenarios like flash sales.

Disadvantages:

- Complex Parameter Tuning: The token generation rate and bucket capacity require precise adjustment based on traffic patterns. Incorrect settings may lead to excessive request denials (if the rate is too low) or system overload (if capacity is too high). For example, an improperly tuned bucket in a flash sale may reject legitimate users or overwhelm servers.

- Risk of Short-Term Overload: A burst consuming all tokens may allow subsequent requests to pass briefly, causing momentary traffic spikes beyond the intended rate. For instance, a target of 100 requests/sec might see 120 requests in a second during a burst.

Use Cases:

- E-commerce Flash Sales: Limiting 1000 purchase requests per second during Alibaba’s Double 11.

- API Requests: Restricting 100 post submissions per minute on X.

- AI APIs: Capping 10 model invocations per second for OpenAI.

Java Implementation:

public class TokenBucket {

private final long capacity; // Maximum number of tokens the bucket can hold

private final double rate; // Token generation rate (tokens per second)

private double tokens; // Current number of available tokens

private long lastRefillTimestamp; // Timestamp of last token refill

// Initialize bucket with capacity and rate, starting with full tokens

public TokenBucket(long capacity, double rate) {

this.capacity = capacity;

this.rate = rate;

this.tokens = capacity;

this.lastRefillTimestamp = System.nanoTime();

}

// Check if request is allowed, thread-safe

public synchronized boolean allowRequest() {

refill(); // Replenish tokens based on elapsed time

if (tokens >= 1) { // Sufficient tokens available

tokens -= 1; // Consume one token

return true; // Allow request

}

return false; // No tokens, deny request

}

// Replenish tokens based on elapsed time

private void refill() {

long now = System.nanoTime();

double elapsedSeconds = (now - lastRefillTimestamp) / 1e9; // Time elapsed in seconds

tokens = Math.min(capacity, tokens + elapsedSeconds * rate); // Add tokens, capped at capacity

lastRefillTimestamp = now; // Update refill timestamp

}

}

Usage Example:

TokenBucket bucket = new TokenBucket(100, 10); // Capacity 100, 10 tokens/sec

for (int i = 0; i < 150; i++) {

if (bucket.allowRequest()) {

System.out.println("Request " + i + " allowed");

} else {

System.out.println("Request " + i + " rejected");

}

}

Parameter Tuning:

- Rate: Set to the average request rate (e.g., 10 requests/sec).

- Capacity: Set to the maximum burst size (e.g., 100 requests).

2. Leaky Bucket

Accessible Explanation:

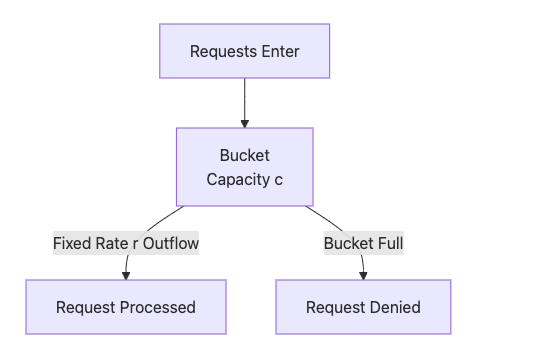

The leaky bucket resembles a container with a fixed-size hole at the bottom. Requests flow into the bucket like water, but they can only exit (be processed) at a constant rate through the hole. If requests arrive too quickly, the bucket fills, and new requests are discarded, ensuring a steady processing rate.

Principle: Requests enter the bucket and are processed at a fixed rate. If the bucket is full, new requests are rejected. This is ideal for stable traffic scenarios.

Mermaid Diagram:

Advantages:

- Stable Output: Processes requests at a consistent rate, protecting downstream systems from traffic surges.

- Memory Efficient: Requires only a queue to store requests, minimizing memory usage.

Disadvantages:

- No Support for Bursty Traffic: The fixed outflow rate cannot accommodate sudden traffic spikes, leading to request rejections. For example, during a flash sale, high-concurrency requests may be denied, degrading user experience.

- Increased Request Latency: Sustained high request rates cause requests to queue in the bucket, increasing processing delays. For instance, API requests may experience response times escalating from seconds to minutes due to queuing.

Use Cases:

- E-commerce APIs: Limiting 50 order requests per second for Shopify.

- Message Queues: Ensuring consistent message processing rates.

Java Implementation:

import java.util.LinkedList;

import java.util.Queue;

public class LeakyBucket {

private final long capacity; // Maximum number of requests the bucket can hold

private final double rate; // Outflow rate (requests processed per second)

private final Queue<Long> queue; // Stores request arrival timestamps

private long lastLeakTimestamp; // Timestamp of last outflow

// Initialize bucket with capacity and outflow rate

public LeakyBucket(long capacity, double rate) {

this.capacity = capacity;

this.rate = rate;

this.queue = new LinkedList<>();

this.lastLeakTimestamp = System.nanoTime();

}

// Check if request is allowed, thread-safe

public synchronized boolean allowRequest() {

leak(); // Perform outflow to process requests

if (queue.size() < capacity) { // Bucket has space

queue.offer(System.nanoTime()); // Add request

return true; // Allow request

}

return false; // Bucket full, deny request

}

// Process outflow based on elapsed time

private void leak() {

long now = System.nanoTime();

double elapsedSeconds = (now - lastLeakTimestamp) / 1e9; // Time elapsed in seconds

int leaked = (int) (elapsedSeconds * rate); // Number of requests that can outflow

while (leaked > 0 && !queue.isEmpty()) { // Remove processed requests

queue.poll();

leaked--;

}

lastLeakTimestamp = now; // Update outflow timestamp

}

}

Usage Example:

LeakyBucket bucket = new LeakyBucket(50, 5); // Capacity 50, 5 requests/sec

for (int i = 0; i < 100; i++) {

if (bucket.allowRequest()) {

System.out.println("Request " + i + " allowed");

} else {

System.out.println("Request " + i + " rejected");

}

}

Parameter Tuning:

- Rate: Match the downstream processing capability (e.g., 5 requests/sec).

- Capacity: Set based on acceptable latency (e.g., 50 requests).

3. Fixed Window Counter

Accessible Explanation:

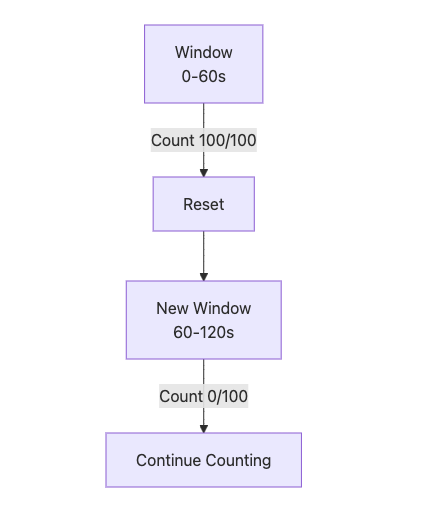

The fixed window counter is like a venue with a limited number of entry passes per hour. Once the passes are exhausted, new entrants must wait for the next hour. Its simplicity is effective, but pass distribution can cluster at window boundaries, causing short-term overloads.

Principle: Counts requests within a fixed time window, rejecting those exceeding the quota. The counter resets at the end of each window.

Mermaid Diagram:

Advantages:

- Simple Implementation: Requires only counting and comparison, enabling rapid development for basic rate limiting.

- Memory Efficient: Stores a single counter, minimizing memory requirements.

Disadvantages:

- Window Boundary Overload: At window transitions (e.g., 59s to 61s), requests may cluster, doubling the intended rate momentarily. For example, a limit of 100 requests per minute could see 99 requests at 59s and 99 at 61s, resulting in 198 requests in 2 seconds, overwhelming the system.

Use Cases:

- Login Restrictions: Limiting 5 login attempts per minute.

- Simple APIs: Restricting 1000 calls per hour for small-scale services.

Java Implementation:

public class FixedWindowCounter {

private final long windowSize; // Window size in milliseconds

private final long limit; // Maximum requests allowed in window

private long windowStart; // Start time of current window

private long count; // Current request count in window

// Initialize window with size and limit

public FixedWindowCounter(long windowSizeSeconds, long limit) {

this.windowSize = windowSizeSeconds * 1000;

this.limit = limit;

this.windowStart = System.currentTimeMillis();

this.count = 0;

}

// Check if request is allowed, thread-safe

public synchronized boolean allowRequest() {

long now = System.currentTimeMillis();

if (now > windowStart + windowSize) { // Window has expired

windowStart = now; // Reset window

count = 0; // Reset counter

}

if (count < limit) { // Within limit

count++; // Increment counter

return true; // Allow request

}

return false; // Exceeds limit, deny request

}

}

Usage Example:

FixedWindowCounter counter = new FixedWindowCounter(60, 5); // 60 seconds, 5 requests

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i++) {

if (counter.allowRequest()) {

System.out.println("Request " + i + " allowed");

} else {

System.out.println("Request " + i + " rejected");

}

}

Parameter Tuning:

- Window Size: Smaller windows (e.g., 10 seconds) reduce boundary issues.

- Limit: Set based on business requirements (e.g., 5 requests/minute).

4. Sliding Window Log

Accessible Explanation:

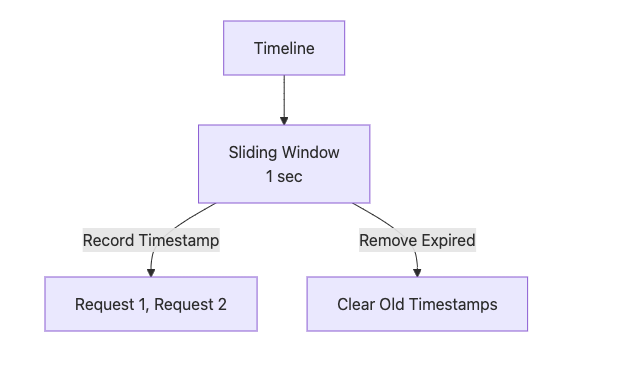

The sliding window log is like a meticulous registrar, recording the exact timestamp of each request. When a new request arrives, it checks the number of requests within the recent time window, denying those exceeding the limit. Its precision is unparalleled, but it demands significant record-keeping.

Principle: Records timestamps of requests and checks the count within a sliding time window, offering high precision.

Mermaid Diagram:

Advantages:

- High Precision: Tracks exact request times, ideal for strict rate-limiting scenarios like financial transactions.

- No Boundary Issues: Smooth sliding window avoids fixed window boundary overloads.

Disadvantages:

- High Memory Usage: Each request’s timestamp is stored, leading to substantial memory consumption in high-concurrency scenarios. For example, 1000 requests per second in a 1-second window require storing 1000 timestamps.

- Complex Implementation: Managing a timestamp queue and removing expired entries increases code complexity and performance overhead. For instance, frequent cleanup in high-traffic scenarios may degrade system performance.

Use Cases:

- Financial Transactions: Limiting 1000 trading requests per second in stock exchanges.

- Ad Bidding: Restricting 500 bids per second in real-time bidding platforms.

- Web3: Controlling blockchain transaction rates.

Java Implementation:

import java.util.LinkedList;

import java.util.Queue;

public class SlidingWindowLog {

private final long windowSize; // Window size in milliseconds

private final long limit; // Maximum requests allowed in window

private final Queue<Long> requests; // Stores request timestamps

// Initialize window with size and limit

public SlidingWindowLog(long windowSizeSeconds, long limit) {

this.windowSize = windowSizeSeconds * 1000;

this.limit = limit;

this.requests = new LinkedList<>();

}

// Check if request is allowed, thread-safe

public synchronized boolean allowRequest() {

long now = System.currentTimeMillis();

// Remove timestamps outside the window

while (!requests.isEmpty() && now - requests.peek() > windowSize) {

requests.poll();

}

if (requests.size() < limit) { // Within limit

requests.offer(now); // Record current request timestamp

return true; // Allow request

}

return false; // Exceeds limit, deny request

}

}

Usage Example:

SlidingWindowLog log = new SlidingWindowLog(1, 10); // 1 second, 10 requests

for (int i = 0; i < 15; i++) {

if (log.allowRequest()) {

System.out.println("Request " + i + " allowed");

} else {

System.out.println("Request " + i + " rejected");

}

}

Parameter Tuning:

- Window Size: Set based on precision needs (e.g., 1 second).

- Limit: Set based on peak traffic (e.g., 1000 requests).

5. Sliding Window Counter

Accessible Explanation:

The sliding window counter is like a theme park queue manager tasked with limiting a roller coaster to 10 riders per minute. Instead of recording each rider’s exact arrival time, the manager divides time into 10-second sub-windows (6 sub-windows covering 60 seconds) and tracks the number of riders in each. When a new rider arrives, the manager estimates the total number of riders in the past 60 seconds by weighting each sub-window’s count based on how much of it remains in the time window: older sub-windows contribute less (“discounted”), while newer ones contribute fully. If the estimated total is below 10, the rider is allowed to join the queue, and the current sub-window’s count is updated; otherwise, they are denied. This approach is memory-efficient and smooths traffic peaks but may introduce slight inaccuracies due to estimation.

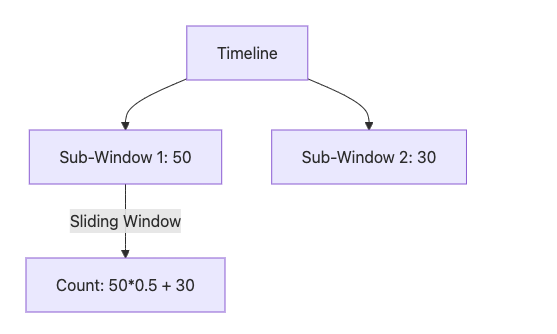

Principle: Divides the time window (e.g., 60 seconds) into smaller sub-windows (e.g., 10 seconds each) and records request counts per sub-window. For a new request, it calculates the total requests in the sliding window using weighted estimation (based on the sub-window’s remaining time proportion). If the total is below the limit, the request is allowed, and the current sub-window’s count is incremented; otherwise, it is rejected. The weighting mechanism simulates a sliding window, avoiding the boundary issues of fixed windows.

Mermaid Diagram:

Advantages:

-

Memory Efficient: Stores only sub-window counts (e.g., 6 sub-windows), reducing memory usage compared to timestamp storage.

-

Smooths Traffic Peaks: Weighted estimation mitigates the boundary overload issues of fixed window counters.

Disadvantages:

- Limited Precision: Weighted estimation may introduce inaccuracies, leading to less strict rate limiting. For example, requests at sub-window boundaries may be partially counted, causing the actual traffic to slightly exceed or fall below the intended limit, impacting high-precision scenarios.

Use Cases:

-

E-commerce Promotions: Limiting 2000 requests per second during JD 618 sales.

-

Social Media Surges: Restricting video uploads during TikTok trending events.

Example: Roller Coaster Queue Limiting

Consider the current time as 12:01:01.000 (61 seconds into the event), with a 60-second window (12:00:01.000 to 12:01:01.000), limiting to 10 riders per minute, and sub-windows of 10 seconds (6 sub-windows). A new rider (Rider 10) arrives, and the manager decides whether to allow them to queue.

Historical Records:

-

12:00:10.000-12:00:20.000: 2 riders.

-

12:00:20.000-12:00:30.000: 1 rider.

-

12:00:30.000-12:00:40.000: 2 riders.

-

12:00:40.000-12:00:50.000: 1 rider.

-

12:00:50.000-12:01:00.000: 0 riders.

-

Current Sub-Window (12:01:00.000-12:01:10.000): 1 rider (initial).

Estimation Process:

The manager estimates the total riders in the past 60 seconds by weighting each sub-window’s count based on its remaining time proportion in the window:

| Sub-Window Time | Riders | Window Proportion (Weight) | Weighted Riders (Riders × Weight) | Notes |

| 12:00:10.000-12:00:20.000 | 2 | 10/60 ≈ 0.167 | 2 × 0.167 ≈ 0.33 | 10 seconds remain in window, small weight, 2 riders contribute 0.33. |

| 12:00:20.000-12:00:30.000 | 1 | 20/60 ≈ 0.333 | 1 × 0.333 ≈ 0.33 | 20 seconds remain, moderate weight, 1 rider contributes 0.33. |

| 12:00:30.000-12:00:40.000 | 2 | 30/60 = 0.5 | 2 × 0.5 = 1.0 | 30 seconds remain, half weight, 2 riders contribute 1.0. |

| 12:00:40.000-12:00:50.000 | 1 | 40/60 ≈ 0.667 | 1 × 0.667 ≈ 0.67 | 40 seconds remain, larger weight, 1 rider contributes 0.67. |

| 12:00:50.000-12:01:00.000 | 0 | 50/60 ≈ 0.833 | 0 × 0.833 = 0 | 50 seconds remain, no riders, contributes 0. |

| Current (12:01:00.000-10.000) | 1 | 60/60 = 1.0 | 1 × 1.0 = 1.0 | Fully in window, full weight, 1 rider contributes 1.0. |

| Total | 3.33 ≈ 3 riders | Estimated 3 riders < 10, allow Rider 10 to queue. |

Role of Weights:

The weight (remaining time proportion) simulates a sliding window: older sub-windows (e.g., 10-20 seconds) contribute less (0.167) as they are nearly out of the window, while newer sub-windows (current) contribute fully (1.0). This smooths traffic peaks, avoiding the abrupt resets of fixed window counters (e.g., 10 riders at 59s + 10 at 61s). The estimation may introduce slight inaccuracies (e.g., 3.33 vs. actual 3.5 riders), suitable for scenarios tolerating minor deviations.

Java Implementation:

import java.util.HashMap;

import java.util.Map;

public class SlidingWindowCounter {

private final long windowSize; // Window size in milliseconds

private final long limit; // Maximum requests allowed in window

private final long subWindowSize; // Sub-window size in milliseconds

private final Map<Long, Long> windows; // Sub-window counts (timestamp -> count)

// Initialize window with size, limit, and sub-window granularity

public SlidingWindowCounter(long windowSizeSeconds, long limit, int granularity) {

this.windowSize = windowSizeSeconds * 1000;

this.limit = limit;

this.subWindowSize = windowSize / granularity;

this.windows = new HashMap<>();

}

// Check if request is allowed, thread-safe

public synchronized boolean allowRequest() {

long now = System.currentTimeMillis();

// Align current time to sub-window start

long gridNumber = now / subWindowSize; // Sub-window index

long currentSubWindow = gridNumber * subWindowSize; // Sub-window start time

// Remove expired sub-windows (older than window size)

windows.entrySet().removeIf(entry -> now - entry.getKey() * subWindowSize > windowSize);

// Calculate total requests in sliding window (weighted estimation)

double total = 0;

for (Map.Entry<Long, Long> entry : windows.entrySet()) {

long subWindowStart = entry.getKey() * subWindowSize; // Sub-window start time

long count = entry.getValue(); // Sub-window request count

// Calculate weight: proportion of sub-window within the window

double weight = Math.min(1.0, (double) (windowSize - (now - subWindowStart)) / windowSize);

total += count * weight; // Weighted count

}

if (total < limit) { // Within limit

// Increment current sub-window count

windows.merge(currentSubWindow, 1L, Long::sum);

return true; // Allow request

}

return false; // Exceeds limit, deny request

}

}

Usage Example:

SlidingWindowCounter counter = new SlidingWindowCounter(60, 10, 6); // 60 seconds, 10 requests, 6 sub-windows

for (int i = 0; i < 15; i++) {

if (counter.allowRequest()) {

System.out.println("Request " + i + " allowed");

} else {

System.out.println("Request " + i + " rejected");

}

}

Parameter Tuning:

-

Window Size: Typically 1–60 seconds, 60 seconds in the example.

-

Granularity: Smaller granularity (e.g., 6 or 10) improves precision, 6 in the example (10 seconds/sub-window).

-

Limit: Set based on business needs (e.g., 10 requests/minute).

Summary

- Selection Guide:

- Bursty Traffic: Token Bucket (handles high concurrency), Sliding Window Counter (smooths peaks).

- Stable Rates: Leaky Bucket (ensures consistent output).

- High Precision: Sliding Window Log (strict limiting).

- Simple Scenarios: Fixed Window Counter (quick implementation).

- Key Considerations:

- Token Bucket: Balances burst support with tuning challenges.

- Leaky Bucket: Prioritizes stability but struggles with bursts and latency.

- Fixed Window Counter: Efficient but prone to boundary issues.

- Sliding Window Log: Precise yet resource-intensive, ideal for critical applications.

- Sliding Window Counter: Efficient with moderate precision, suitable for balanced needs.

- Practical Recommendations:

- Use Redis for distributed environments (e.g., Token Bucket, Fixed Window).

- Test under high concurrency to validate rate-limiting effectiveness.

- Monitor request rates and adjust parameters dynamically.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: