Technical Guide to Distributed Unique IDs

- 1. The Need for Distributed, Globally Unique IDs

- 2. Common Distributed ID Generation Schemes

- 3. A Milestone: Twitter’s Snowflake Algorithm

- 4. Industry Evolutions and Variants

- 5. Solution Comparison and Conclusion

1. The Need for Distributed, Globally Unique IDs

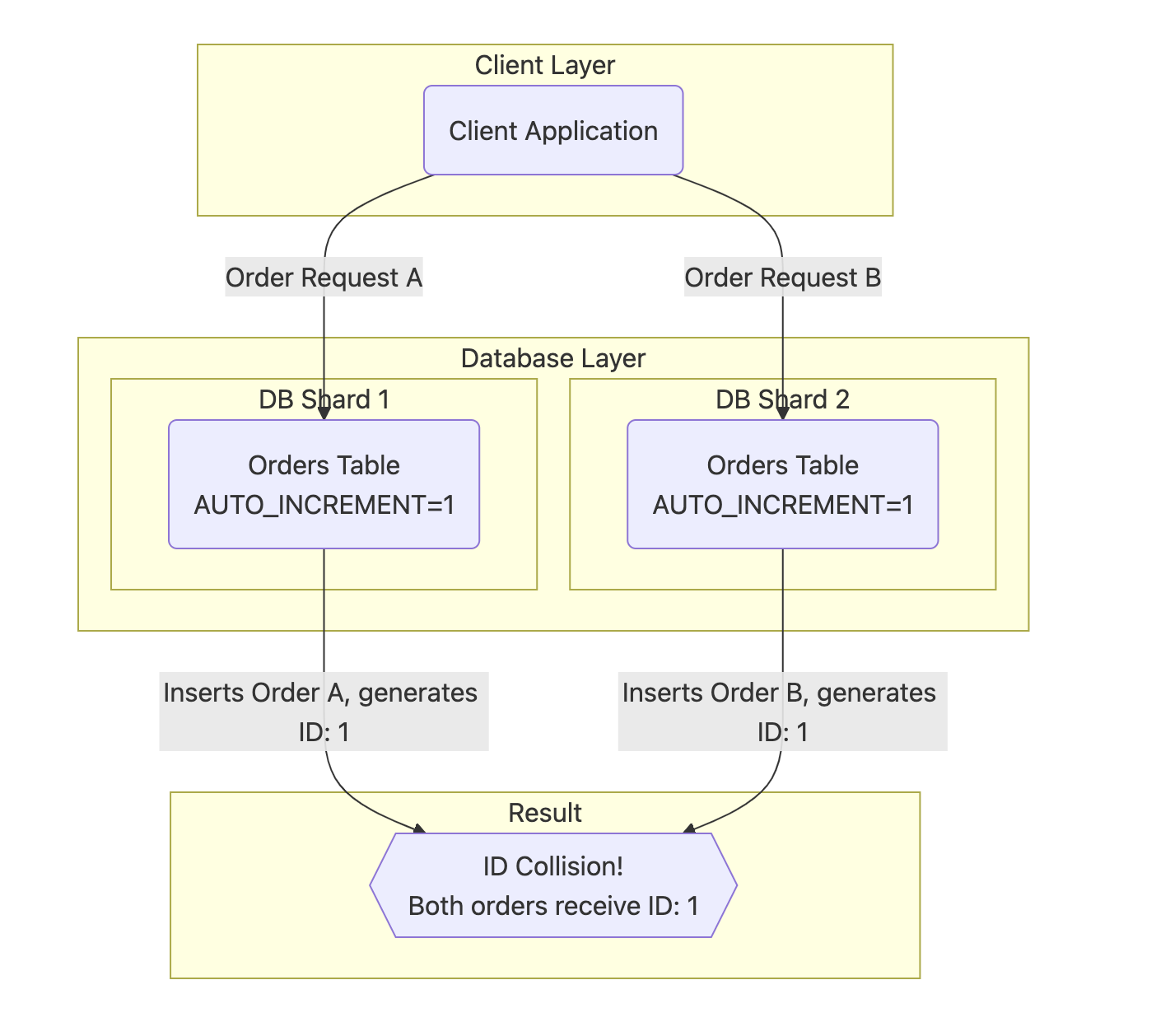

In traditional monolithic architectures, systems typically rely on a single database. The primary keys for business tables are often generated using the database’s AUTO_INCREMENT feature. This method is simple, reliable, and guarantees uniqueness within that single database.

However, in modern distributed and microservices architectures, systems are often partitioned to handle high concurrency and massive data volumes. This means that data for a single business entity, such as “orders,” is spread across multiple database instances or tables. In such a scenario, if each shard independently uses its own AUTO_INCREMENT mechanism, ID collisions become inevitable, as illustrated below:

Although the system architecture is distributed, at the business logic and user level, an order ID must be globally unique. Duplicate primary keys are unacceptable.

Therefore, designing a high-performance, highly available, and globally unique ID generation scheme is a foundational requirement for any distributed system. This document provides an in-depth analysis of common distributed ID generation solutions.

2. Common Distributed ID Generation Schemes

2.1. UUID (Universally Unique Identifier)

A UUID is a 128-bit number used to identify information in computer systems. The theoretical number of possible UUIDs is 2^128, making collisions practically impossible for the foreseeable future. The standard format is 8-4-4-4-12, though hyphens are often removed in practice.

Key UUID Versions:

- Version 1 (Time-based): Generated from a timestamp, a random number, and the local MAC address. While unique, it can expose the MAC address, posing a security risk.

- Version 2 (DCE Security): Similar to Version 1, but replaces parts of the timestamp with POSIX UID/GID. It is rarely used.

- Version 3 (Name-based, MD 5): Generated from the MD 5 hash of a namespace and a name. It is deterministic: the same input produces the same UUID.

- Version 4 (Random): Generated from random or pseudo-random numbers. This is the most common version, and it’s what

UUID.randomUUID()in Java generates. - Version 5 (Name-based, SHA-1): Similar to Version 3 but uses the SHA-1 hashing algorithm.

Java Code Example:

import java.util.UUID;

public class UuidExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Version 4: Random UUID

UUID randomUuid = UUID.randomUUID();

System.out.println("Random UUID: " + randomUuid.toString().replaceAll("-", ""));

// Version 3: Name-based UUID

byte[] nameBytes = "hello-world".getBytes();

UUID nameUuid = UUID.nameUUIDFromBytes(nameBytes);

System.out.println("Name-based UUID: " + nameUuid.toString().replaceAll("-", ""));

}

}

Analysis:

- Pros:

- Local Generation: Extremely high performance as no network requests are needed.

- Global Uniqueness: The probability of collision is infinitesimally small.

- Simplicity: Natively supported in most languages, often requiring just a single line of code.

- Cons:

- Storage Inefficiency: UUIDs are long strings (36 characters with hyphens), consuming more storage space than numerical IDs.

- Poor Indexing Performance: UUIDs are non-sequential. Using them as primary keys in database engines like InnoDB (which uses B+ trees) leads to frequent index page splits and random data inserts, severely degrading write performance.

- Lack of Readability: The ID itself is opaque and carries no discernible information.

2.2. Database Auto-Increment Scheme

This scheme extends the single-database auto-increment concept to a distributed environment through careful configuration.

Core Idea: Configure each database instance with a different starting value (offset) and a common step (increment).

For example, with three MySQL servers, the configuration could be:

- DB 1:

auto_increment_offset=1,auto_increment_increment=3→ Generated IDs: 1, 4, 7, 10, … - DB 2:

auto_increment_offset=2,auto_increment_increment=3→ Generated IDs: 2, 5, 8, 11, … - DB 3:

auto_increment_offset=3,auto_increment_increment=3→ Generated IDs: 3, 6, 9, 12, …

Analysis:

- Pros:

- Simple Implementation: Requires only database configuration, no extra components.

- Ordered IDs: Generates numeric, incrementally ordered IDs, which are friendly to database indexes.

- Cons:

- Strong Database Dependency: The database becomes a performance bottleneck and a single point of failure for ID generation.

- Poor Scalability: Adding or removing database instances is a high-risk operation, requiring recalculation and reconfiguration across all instances.

- Consistency Risks: In scenarios like master-slave failover, there’s a risk of data inconsistency that could lead to duplicate IDs.

2.3. Redis Atomic Increment Scheme

Redis provides atomic commands like INCR and INCRBY. Because Redis executes commands in a single-threaded manner, it naturally guarantees the uniqueness and order of generated IDs.

Core Idea: Use Redis’s atomic operations to generate a globally unique sequence.

Implementation: For each ID request, a client sends an INCR a_unique_key command to Redis. To prevent the ID from growing indefinitely, it’s often combined with a business prefix or a timestamp.

Analysis:

- Pros:

- High Performance: Operations are in-memory and significantly faster than a database.

- Ordered IDs: The generated IDs are strictly increasing.

- Cons:

- Introduces a New Component: Requires the introduction and maintenance of Redis, increasing architectural complexity.

- Strong Redis Dependency: The availability of the ID service is tied to Redis. A highly available Redis cluster (e.g., Sentinel or Cluster mode) is necessary to mitigate this.

- Network Overhead: Every ID generation requires a network round-trip, which can be a significant cost under high concurrency.

3. A Milestone: Twitter’s Snowflake Algorithm

The previous solutions all have significant drawbacks. In 2010, Twitter open-sourced its Snowflake algorithm, an elegant solution for generating IDs locally in a distributed environment. It has since become the foundational model for many modern distributed ID schemes.

3.1. Core Idea and ID Structure

Snowflake’s core idea is to partition a 64-bit long integer into several sections at the binary level, with each section having a specific meaning. This allows each node to generate globally unique IDs locally, without communicating with other nodes.

A standard Snowflake ID is structured as follows:

| Section | Sign Bit | Timestamp | Datacenter ID | Worker ID | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bits | 1 bit | 41 bits | 5 bits | 5 bits | 12 bits |

| Meaning | Fixed to 0 (for positive IDs) | Millisecond timestamp offset | Identifies the datacenter | Identifies the node/machine | Intra-millisecond counter |

Conceptual Analogy:

Think of the Snowflake algorithm as a system for minting highly precise, unique identification cards.

- The 64-bit ID is the blank ID card.

- The Timestamp (41 bits) is the “Date of Issue,” precise to the millisecond. It defines the “era” of the ID and is its most significant part.

- The Datacenter ID (5 bits) is the “Issuing Province.”

- The Worker ID (5 bits) is the specific “Issuing City Office” within that province.

- The Sequence (12 bits) is the “Serial Number” issued by that specific office within the same millisecond.

By combining the time of issue + location of issue (province + city) + local serial number, this system guarantees that every ID card produced is globally unique.

3.2. Detailed Breakdown of Each Section

3.2.1. Sign Bit (1 bit)

The most significant bit of a long in Java is the sign bit. It is fixed to 0 to ensure all generated IDs are positive and to simplify cross-language compatibility.

3.2.2. Timestamp (41 bits)

- Content: This section stores the difference between the

current timestamp (in milliseconds)and acustom epoch timestamp. - The

twepoch: In Twitter’s official implementation, this epoch is set to1288834974657L, which corresponds to Nov 04, 2010 01:42:54 UTC. - Why a Custom Epoch? 41 bits cannot store the full number of milliseconds since the Unix epoch (Jan 1, 1970). By using a more recent starting point, a large absolute timestamp is converted into a smaller relative one. This allows 41 bits to cover a span of approximately 69 years ($2^{41} / (1000 \cdot 60 \cdot 60 \cdot 24 \cdot 365) \approx 69$ years). The algorithm can thus be used until around the year 2079.

3.2.3. Datacenter ID (5 bits) + Worker ID (5 bits) = 10 bits

These 10 bits collectively form the worker node ID, distinguishing different ID generation nodes.

- Capacity:

- Datacenter ID (5 bits): Supports $2^5 = 32$ datacenters.

- Worker ID (5 bits): Supports $2^5 = 32$ machines per datacenter.

- This allows for a total of $32 \times 32 = 1024$ nodes.

- Allocation Mechanism: Manually configuring worker IDs in a dynamic cloud environment is infeasible. The standard practice is to rely on a coordination service like ZooKeeper for automatic allocation.

- Process: On startup, a service instance creates an ephemeral sequential node in a designated ZooKeeper path. ZooKeeper assigns a globally unique sequence number to this node, which is then used as the

workerId. - Automatic Reclamation: Because the node is ephemeral, it is automatically deleted if the service instance crashes or loses its connection to ZooKeeper. This allows the

workerIdto be reused by a new instance, preventing ID waste.

3.2.4. Sequence (12 bits)

- Purpose: Resolves collisions when multiple IDs are generated on the same node within the same millisecond.

- Capacity: 12 bits can represent $2^{12} = 4096$ values (0-4095).

- Mechanism:

- The sequence number is incremented for each ID generated within the same millisecond.

- What if the sequence is exhausted (reaches 4095)? The original Snowflake implementation performs a spin-wait, pausing the thread until the next millisecond arrives.

- Once the clock ticks to the next millisecond, the sequence number is reset to

0. - Performance Limit: This design sets the theoretical performance ceiling for a single Snowflake node at 4095 IDs/millisecond, or approximately 4.09 million IDs/second, which is more than sufficient for most use cases.

3.3. The Core Challenge: Clock Skew

This is Snowflake’s most famous “Achilles’ heel.” Server clocks can drift backwards due to NTP synchronization or other reasons.

- Critical Impact: If the clock moves backward, the

current timestampcould be less than thelast recorded timestamp, potentially leading to duplicate IDs and breaking the algorithm’s time-ordered nature. - Twitter’s Original Solution: A Fail-Fast strategy.

- The code detects if the current time is earlier than the last recorded time and immediately throws an exception.

- This means the node becomes unavailable for ID generation until the clock issue is resolved.

- This strategy prioritizes data correctness over availability (“better to be down than to be wrong”).

3.4. Snowflake Summary

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| High Performance: Local generation with low latency. | Strong Clock Dependency: Clock skew is a critical issue. |

| Time-Ordered IDs: IDs are roughly sortable by time. | Requires Coordination Service: Worker ID allocation depends on components like ZooKeeper. |

| Embedded Information: IDs contain timestamp and node data. | Fixed Bit Allocation: The 1024-node limit can be a constraint in large-scale deployments. |

| Numeric Type: Efficient storage and querying as a 64-bit long. | Frontend Overflow Risk: JavaScript cannot precisely handle 64-bit integers. |

4. Industry Evolutions and Variants

While Snowflake’s design is brilliant, its complexity in worker ID allocation and its vulnerability to clock skew left room for improvement. Major tech companies like Baidu and Meituan have developed and open-sourced their own enhanced solutions.

4.1. Baidu’s UidGenerator: Engineered for Performance and Ease of Use

UidGenerator is an open-source ID generator from Baidu that improves upon Snowflake with a focus on usability and concurrent performance.

4.1.1. Core Design: A Restructured ID (1-28-22-13)

UidGenerator significantly alters the 64-bit structure, changing the time unit from milliseconds to seconds.

| Section | Sign Bit | Delta Seconds | Worker ID | Sequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bits | 1 bit | 28 bits | 22 bits | 13 bits |

- Timestamp (28 bits, seconds):

- Sacrifice: The usable lifespan is reduced from 69 years to approximately 8.5 years ($2^{28}$ seconds). This is a major trade-off that requires careful system lifecycle planning.

- Gain: Frees up

41 - 28 = 13bits for other sections. - Worker ID (22 bits):

- Pain Point Solved: Supports $2^{22}$ (over 4 million) nodes. This completely resolves the

workerIdlimitation of classic Snowflake, making it highly suitable for containerized cloud environments with frequent instance churn. - Sequence (13 bits):

- Capacity: Supports $2^{13} = 8192$.

- Meaning: Allows for 8192 unique IDs to be generated per second on a single node.

4.1.2. Worker ID Allocation: From ZooKeeper to the Database

UidGenerator replaces the ZooKeeper dependency with a component that nearly every project already has: a database.

- Implementation: On startup, the service inserts a record into a

WORKER_NODEtable containing its host and port. The auto-incremented primary key generated by the database for this record is used as theworkerId. - Advantage: Drastically reduces operational overhead and technology stack complexity, as there is no need to maintain a ZK cluster.

- Disadvantages:

- Startup Dependency on DB: New instances cannot start if the database is down.

- ID Waste: The default strategy consumes a new

workerIdon every restart.

4.1.3. The Performance Weapon: CachedUidGenerator and the RingBuffer

This is the core of UidGenerator and its recommended mode of operation. It uses a “space-for-time” trade-off to deliver extreme performance.

- Core Idea: Pre-generation and caching of IDs. This decouples the “production” of IDs from their “consumption.”

- The RingBuffer:

- Producer: A background thread asynchronously generates IDs in batches and populates a RingBuffer (a circular array).

- Consumer: When a business thread requests an ID, it does not compute it on the spot. Instead, it retrieves one from the RingBuffer lock-free (via CAS atomic operations).

Conceptual Analogy:

CachedUidGeneratoroperates like a highly efficient, modern coffee shop.

- Business Requests are the customers.

- The RingBuffer is a large, pre-filled dispenser of freshly brewed coffee.

- Getting an ID (Consumption): A customer orders, and the barista instantly dispenses a cup from the machine. The process is immediate, with no waiting.

- The Background Thread (Production): A staff member in the back is constantly monitoring the coffee level in the dispenser. When it drops below a certain threshold (e.g., 50%), they brew a large new batch and quickly refill the machine.

Through this “front-of-house for sales, back-of-house for preparation” model, the customer (the business logic) experiences lightning-fast service, completely unaware of the “time-consuming” brewing process. This is the secret to

CachedUidGenerator‘s high performance.

- Benefits:

- Extreme Performance: The business thread’s action is reduced to a memory access operation with virtually no lock contention, resulting in massive throughput.

- Eliminates Jitter: It smooths out the performance “hiccups” that can occur at time boundaries (e.g., the start of a new second) in other implementations.

- It also employs advanced techniques like Cache-Line Padding to avoid “False Sharing” on multi-core CPUs, demonstrating a commitment to squeezing out every last drop of performance.

4.1.4. The Unresolved Challenge: Clock Skew

On this issue, UidGenerator still adheres to the original “Fail-Fast” strategy, throwing an exception upon detecting clock skew.

4.1.5. UidGenerator Summary

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Exceptional Performance: Cached mode offers lock-free retrieval. | Shorter ID Lifespan: ~8.5 years by default, requires planning. |

| High Usability: Worker ID allocation depends only on a database. | Clock Skew Unresolved: Still uses the fail-fast approach. |

| Massive Worker ID Space: 22 bits support over 4 M nodes. | Potential Worker ID Waste: Restarts consume new IDs by default. |

4.2. Meituan’s Leaf: Engineered for Robustness and High Availability

Leaf is Meituan’s open-source ID service, offering two distinct solutions to cater to different needs: Leaf-segment and Leaf-snowflake.

4.2.1. Leaf-segment: The Ultimate Optimization of Segment Mode

This solution takes a completely different approach from Snowflake, focusing on optimizing the database-based model.

- Core Idea: Database Segment Mode. Instead of fetching one ID at a time, Leaf fetches a large “segment” (or batch) of IDs from the database into memory.

- For example, it might fetch the range

[1, 1000]in a single database transaction. For the next 1000 requests, Leaf serves IDs from memory by simply incrementing a counter, with zero database interaction. - Dual Buffer Mechanism:

- Pain Point Solved: In a simple segment model, there’s a performance jitter when one segment is exhausted and the next one needs to be fetched from the database.

- Leaf’s Solution: It maintains two buffers. While one buffer is actively serving IDs, an asynchronous thread pre-fetches the next segment into the second (standby) buffer once the active buffer’s usage crosses a threshold (e.g., 10%). When the active buffer is depleted, the system instantly and seamlessly switches to the standby buffer.

Conceptual Analogy:

Leaf-segmentis like the ticketing machine at a bank or hospital.

- Getting an ID is a customer pressing a button and taking a ticket.

- A Segment is an entire roll of ticket paper inside the machine (e.g., 1000 tickets).

- Fetching from DB is the lobby manager noticing the paper is low and getting a new roll from the storeroom.

- The Dual Buffer Mechanism means this is an advanced machine with two cartridge slots. While cartridge 1 is in use, the manager is prompted to load a new roll into cartridge 2. When cartridge 1 runs out, the machine instantly switches to cartridge 2, ensuring uninterrupted service.

- High Availability Design: Leaf recommends setting the segment

stepto a multiple of the peak QPS (e.g., enough for 10 minutes). This means that even if the database goes down, Leaf can continue to serve IDs from its in-memory buffers for 10-20 minutes, buying valuable time for database recovery.

4.2.2. Leaf-snowflake: A Hardened Snowflake

This solution enhances the classic Snowflake algorithm, specifically addressing its two major pain points.

- Worker ID Allocation (ZK + Local Cache):

- Still Uses ZooKeeper: Leaf acknowledges ZK’s strengths for initial, unique

workerIdallocation via persistent sequential nodes. - Introduces a Local File Cache: After obtaining a

workerIdfrom ZK, Leaf caches it in a local disk file. - High Availability Impact: On subsequent restarts, Leaf first reads the local file to get its

workerId. It only contacts ZK if the file doesn’t exist. This dramatically reduces its dependency on ZK; a service can restart successfully even if the ZK cluster is down. - Clock Skew Handling (ZK + Proactive Shutdown):

- This is Leaf-snowflake’s most significant contribution. It uses ZK as a “third-party time authority.”

- Detection: Each node periodically reports its timestamp to its ZK node. If it detects its local clock is earlier than the last timestamp it reported, it knows a clock skew has occurred.

- Handling Strategy: The recommended best practice is automatic node removal. * Upon detecting clock skew, the node proactively changes its status to “unavailable” and removes itself from the load balancer’s pool. * Traffic is automatically routed to healthy nodes, ensuring the overall cluster remains available. * Simultaneously, it raises a high-priority alert for operators to investigate the “sick” machine.

Conceptual Analogy:

Leaf-snowflakeis like a highly responsible, experienced chain store manager.

- Worker ID Allocation:

* When opening a new store, the manager calls headquarters (ZooKeeper) to get a permanent **store ID**.

- He immediately makes a copy of the ID and locks it in the store’s safe (local file cache).

- For all future re-openings (restarts), he checks the safe first and doesn’t need to call headquarters, ensuring he can open even if HQ’s phone lines are down.

- Clock Skew Handling:

* The manager notices the clock on his wall is wrong (clock skew).

- Instead of shutting down chaotically (throwing an exception), he quietly flips the “Open” sign to “Under Maintenance” and proactively informs the central delivery platform (load balancer): “Stop sending me orders for now; I have an equipment issue.”

- Customer orders are automatically routed to other stores, and the brand’s overall service is unaffected. Meanwhile, he has already sent a maintenance request to headquarters. This is a model of professional fault handling.

4.2.3. Leaf Summary

Leaf provides two excellent, distinct solutions:

- Leaf-segment: Ideal for scenarios requiring strictly ordered, purely numeric IDs. It offers exceptional performance and availability.

- Leaf-snowflake: A hardened version of Snowflake. It masterfully solves the critical issues of ZK dependency and clock skew, offering extreme robustness.

4.3. The Mist Algorithm: A Timestamp-less Approach

This algorithm takes a radical approach, positing that the dependency on time is the root of all evil. Therefore, it eliminates the timestamp entirely.

- Core Design: Complete decoupling from time.

- Advantage: Completely immune to clock skew. Server time fluctuations have no impact on ID generation, making the system incredibly robust.

- Trade-off: It must rely on an external, centralized service (like Redis) to provide a globally unique, incrementing sequence.

- ID Structure (1-47-8-8):

-

1Sign Bit -

47bits for an incrementing number (from RedisINCR). This guarantees strict ordering and a very long lifespan. -

16bits for random factors. This makes the final ID unpredictable, protecting business data (like order volume) from being easily estimated.

Conceptual Analogy:

The Mist Algorithm is like a central bank issuing currency.

- The ID is a unique banknote.

- The centralized Redis is the one and only national mint. All ID generation instances must request “batch numbers” from it.

- The 47-bit incrementing number is the unique, strictly increasing serial number on each banknote.

- The 16-bit random factor represents the banknote’s security features, like watermarks and security threads. It makes two consecutive serial numbers look completely different, preventing counterfeiting and analysis.

The advantage of this model is absolute authority, security, and immunity to local “clock” inaccuracies. The disadvantage is that if the mint shuts down, the entire nation’s money supply is halted.

- Architectural Trade-off:

- Introduces a Central Bottleneck: The system’s overall performance is capped by the QPS and network latency of the central Redis instance.

- Introduces a Single Point of Failure: If the Redis cluster fails, the entire ID generation service fails.

- Use Cases:

- Scenarios with zero tolerance for clock skew.

- Scenarios requiring unpredictable IDs for security (e.g., financial transactions, e-commerce orders).

- Scenarios where the business QPS is within the limits of a highly available Redis cluster.

5. Solution Comparison and Conclusion

| Scheme | ID Trend | Performance | Core Dependency | WorkerID Allocation | Clock Skew Handling | Key Advantage | Core Drawback |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UUID | Unordered | Extreme (Local) | None | N/A | Irrelevant | Simplicity, no network cost | String, unordered, poor index perf |

| DB Auto-Inc | Strictly Inc | Low | Database | N/A | Irrelevant | Simplicity, ordered IDs | DB dependency, poor scalability |

| Redis Inc | Strictly Inc | High | Redis | N/A | Irrelevant | Good performance, ordered IDs | Redis dependency, network cost |

| Snowflake | Time-ordered | Extreme (Local) | ZooKeeper | ZK Ephemeral Node | Throws Exception | Balanced performance, embedded info | Strong clock dependency, ZK complexity |

| UidGenerator | Time-ordered | Ultimate (Local) | Database | DB Auto-Inc ID | Throws Exception | Extreme performance, massive WorkerID space | Short lifespan (~8.5 yrs), clock skew unresolved |

| Leaf-segment | Strictly Inc | Extreme (Mem) | Database | N/A | Irrelevant | Smooth perf, HA, sequential IDs | Predictable IDs, DB dependency |

| Leaf-snowflake | Time-ordered | Extreme (Local) | ZooKeeper | ZK + Local Cache | Proactive Shutdown | Extreme Robustness, solves clock skew | ZK dependency, slightly complex |

| Mist | Strictly Inc | High (Limited) | Redis | N/A | Immune | Clock immune, unpredictable IDs | Centralized dependency & bottleneck |

Conclusion:

There is no “best” distributed ID solution, only the one that is “most suitable” for your specific context.

- For simplicity and rapid integration where ID order is not critical, UUID is an option.

- For a high-performance, time-ordered, and information-rich ID, Snowflake is the classic benchmark.

- To build on that with a focus on extreme ease-of-use and massive node support (while accepting a limited lifespan), Baidu’s UidGenerator is an excellent choice.

- For systems with the highest requirements for robustness and availability, especially for gracefully handling clock skew, Meituan’s Leaf-snowflake is arguably the most complete solution in the industry.

- If your business requires strictly sequential, purely numeric IDs, Meituan’s Leaf-segment offers unparalleled performance and smoothness.

- Finally, if clock safety and ID unpredictability are paramount, and you can accept the architectural cost of centralization, the Mist algorithm provides a novel and effective alternative.

When making a selection, always consider your application’s QPS, requirements for ID format and order, your team’s operational capabilities, and the specific trade-offs you are willing to make between availability and data consistency.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: